Volcanoes

Volcano Types

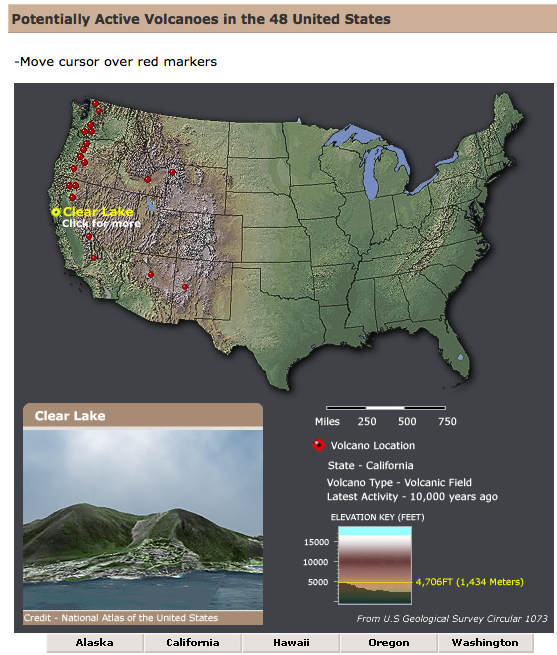

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that there are about 65 active volcanoes in the United States and its territories. The Dynamic maps viewer (shown at right) provides an interactive presentation of potentially active volcanoes in the 48 continguous states.

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that there are about 65 active volcanoes in the United States and its territories. The Dynamic maps viewer (shown at right) provides an interactive presentation of potentially active volcanoes in the 48 continguous states.

Volcanoes are distinguished by their eruption style, composition, and structure. Volcanoes act differently and form differently because they are made up of different types of rocks and minerals. Below is a description of common volcano types that can be recognized as distinguishable land formations.

For more than 200 years keen observers have noted that some volcanic eruptions affect weather and climate. Scientists report that large eruptions at low latitudes can cause the greatest global climate change. Weaker eruptions send their eruptive materials only into the troposphere, where wind and rain quickly remove them. High latitude eruptions send their materials into only one hemisphere.

Based on this information and the nature of different volcano types presented below, do you think that certain types of volcanoes are more likely to cause climate change when they erupt? See if you can answer this question as you investigate the relationship between volcanoes and climate change.

Volcanoes have many shapes and sizes, but the following three types are most important: stratovolcanoes, shields, and supervolcanoes. Use the Dynamic map tool to find further illustrations of volcanoes described in this overview of volcano types.

Stratovolcanoes (Composite Volcanoes)

Many of Earth's most beautiful mountains are stratovolcanoes—also referred to as composite volcanoes. The stratovolcanoes are made up of layers of lava flows interlayed with sand- or gravel-like volcanic rock called cinders or volcanic ash. These volcano land formations are typically 10-20 miles across and up to 10,000 or more feet tall. This type of volcano has steeper slopes of 6-10 degrees on its flanks and as much as a 30 degree slope near the top. Stratovolcanoes show interlayering of lava flows and typically up to 50 percent pyroclastic material, which is why they are sometimes called composite volcanoes.

Pyroclastic flows are high-density mixtures of hot, dry rock fragments and hot gases that move away from the vent that erupted them at high speeds. They may result from the explosive eruption of molten or solid rock fragments, or both. They may also result from the nonexplosive eruption of lava when parts of dome or a thick lava flow collapses down a steep slope. Most pyroclastic flows consist of two distinguishable flowing mixtures: a basal flow of coarse fragments that moves along the ground and a turbulent cloud of ash that rises above the basal flow. Ash may fall from this cloud over a wide area downwind from the pyroclastic flow.

Referring to the images below, the diagram shows how a composite or stratovolcano is “built” on the inside, and the photograph represents an example of an actual stratovolcano.

|

|

|

Image above at left: A schematic representation of the internal structue of a typical stratovolcano (composite volcano). Image source: USGS publications.

Image above at right: Mayon, a stratovolcano in the Philippines. Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Volcano.

Shield Volcanoes

The second type may be familiar to you from news reports from Hawaii: the shield volcano. This type of volcano can be hundreds of miles across and 10,000 feet high. A shield volcano is characterized by gentle upper slopes (about 5 degrees) with somewhat steeper lower slopes (about 10 degrees). The shield volcanoes are almost entirely composed of relatively thin lava flows built up over a central vent. These features are illustrated in the shield volcano diagram shown below.

Shield volcanoes have small amounts of pyroclastic material, most of which accumulates near the eruptive vents, resulting from fire fuming events. Thus, shield volcanoes typically form from nonexplosive eruptions of low viscosity basaltic magma.

The individual islands of the state of Hawaii are simply large shield volcanoes. Mauna Loa, a shield volcano on the "big" island of Hawaii, is the largest single mountain in the world, rising more than 30,000 feet above the ocean floor and reaching almost 100 miles across at its base. Shield volcanoes have low slopes and consist almost entirely of lavas. They almost always have large calderas at their summits.

|

The graphic at left illustrates the internal structure of a typical shield volcano. Image source: |

|

|

Image at left: Skjaldbreiour, a shield volcano in Iceland. Skjaldbreiour means “broad shield." Image source: |

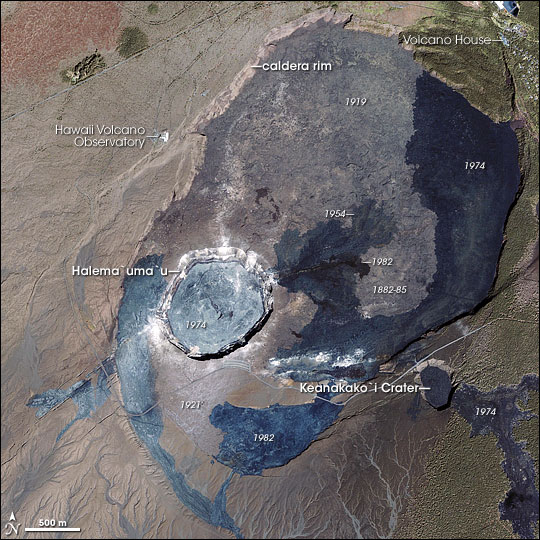

Calderas: A Landform at the Summit of Shield and Stratovolcanoes

Both strato/composite and shield volcanoes can lose their tops following a series of tremendous explosions. The change in these volcanoes' structure is visible as a large depression at the shield or stratovolcano summit. After enormous volumes of volcanic ash and dust are expelled and swept down the slopes as ash and avalanches, these large volume explosions rapidly drain in magna beneath the mountain and can no longer support the volcano top. The collapsing top forms a large depression in the landscape, which may later fill with water to form a lake. Similarly, the tops of shield volcanoes collapse when magma erupts as lava flows, emptying the magma chambers. The steep-walled, basin-shaped depressions formed by the collapse of volcanoes are called calderas. Calderas by definition are larger than 1.5 miles in diameter and can range up to 15 miles wide or as huge elongated depressions as much as 60 miles long. The two images below show two very different caldera land formations.

|

|

|

Image above at left: Crater Lake, Oregon; Wizard Island, a cinder cone, rises above the lake surface. Image source: USGS publications.

Image above at right: This Ikonos image, taken on Jan. 14, 2003, shows Kilauea’s summit caldera, the surface of which is covered in fresh lava flows. The newer flows are dark, while the older flows pale as the iron in the lava oxidizes into rust. The oldest flow in the caldera is from 1882. The Halema`uma`u crater forms a pale circle in the southwest section of the caldera. As recently as 1924, the crater was filled with a molten lava lake. Image source: NASA Earth Observatory.

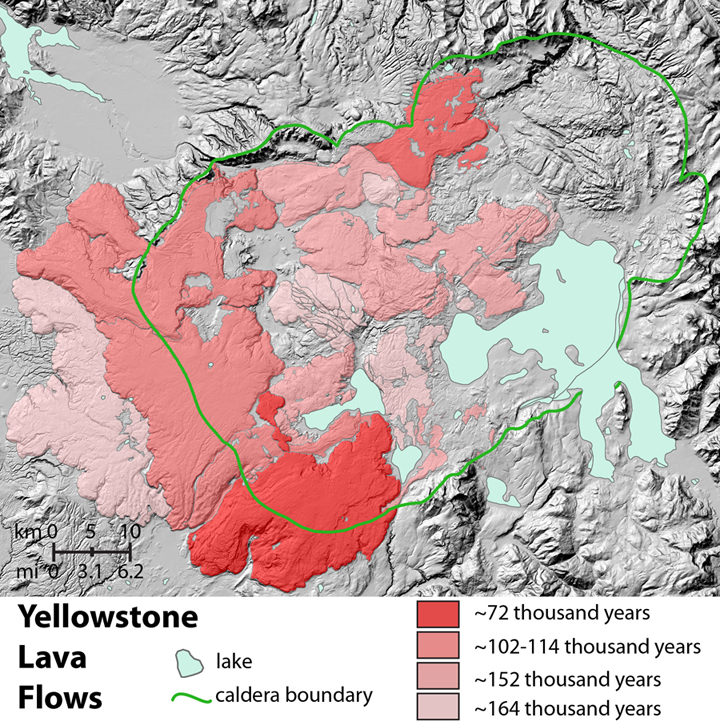

Supervolcanoes

While ordinary volcanoes can kill thousands of people and destroy entire cities, scientists believe that a supervolcano explosion is big enough to affect everyone on the planet. Although they're called "super," most people would have trouble spotting a supervolcano before it erupts. The main feature of supervolcanoes is a large magma chamber, which is an underground reservoir filled with flowing, hot rock under huge pressures. Afer their eruption ash has been blown so far away that no mountain exists, and commonly the area is low and lake-filled.

A supervolcanic eruption is rare. The last one occurred at Toba, Indonesia, about 74,000 years ago. Geologists think these eruptions take place about every 50,000 years. About 40 supervolcanoes are identified across the globe, but fortunately no supervolcano eruption has occured in the last 1,000 years.

Yellowstone, located in Wyoming, is a dormant supervolcano, which means a major eruption could happen in the future.

The Yellowstone National Park lies within the Yellowstone Caldera, a collapse hat formed during a super eruption 640,000 years ago. Heat from magma beneath the caldera still fuels some 10,000 geothermal features (geysers and hot springs)—that's half of the world total.

|

The map above at left of the Yellowstone supervolcano shows the lava flows. The flow is dated to be 72,000 years old and to have erupted as a single event. Other flows were likely formed from multiple eruptions. Photo credit: USGS/Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

The image above at right shows steam rising from Castle Geyser in Yellowstone National Park. Image source: Yellowstone National Park (file photo): Photograph by Mark Thiessen, National Geographic.

Cinder Cone Volcanoes

An easily recognized type of volcano is the cinder cone. As you might expect from the name, these volcanoes consist almost entirely of loose, grainy cinders consisting typically of basaltic and andesitic material and almost no lava. They are small volcanoes, usually only about a mile across and up to about 1,000 feet high. They have very steep sides and usually have a small crater on top. Often cinder cones are classed as a major type of volcano. But cinder cones are much smaller than most shield, composite, and ash flow volcanoes. In fact, cinder cones occur on all of these larger volcano types.

|

|

|

|

Image at left: A schematic representation of the internal structure of a typical cinder cone. Image source: USGS publications. Image at right: Cinder cone volcano near Veyo, Utah. Image source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:VeyoVolcano.jpg. |

More Volcano Types

Maars, lava domes, geysers, fumaroles, hot springs, and pateau basalts are also volcanic land forms caused by different geological processes that form them and control their activities once these different geophysical structures are formed. These and the other volcanic stuctures described above are characterized by the types of materials they are made of, which results from prior eruptive behavior of the volcano. Explore how geologists study and classify volcanic eruptions and landforms with these additional resources:

The Volcano Hazards Program at USGS: http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/hazards/index.php

Earth Observatory: Volcano Images and Features: http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/

Can You Recognize Types of Volcanoes?

What types of volcanoes are seen in this image of Russia’s Kamcharka Peninsula?

Hint: Look closely. There are two stratovolcanoes, one shield volcano, and one volcano that appears to be formed from overlapping stratovolcanoes. View image with volcano types identified in the Volcanoes Featured Data section.

This image was taken by an astronaut of the Expedition 25 crew from the International Space Station.

http://eoimages.gsfc.nasa.gov/images/imagerecords/47000/47514/ISS025-E-017440_lrg.jpg.